It is as easy as breaking your arm after a hard hit in a football

game. It is as easy as landing wrong from a jump and tearing your ACL (anterior

cruciate ligament). Becoming addicted to opiate drugs is as quick and easy as

the doctor who signed you a prescription for them with no intention of turning

your life into a living hell. Thousands of people, including recovering addict,

Johnathan Maresca, are in complete opposition of abusing opiates one day, and

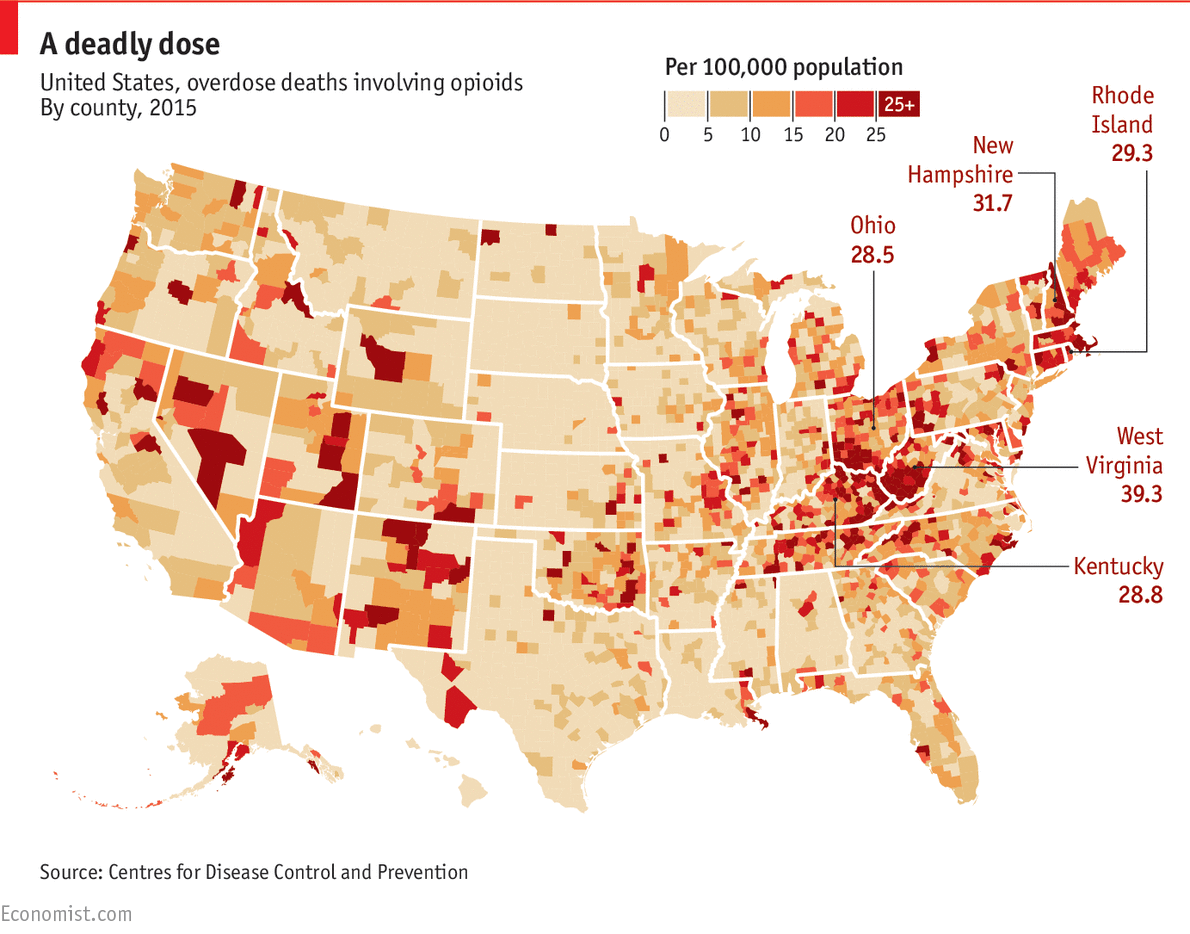

the next they are at risk of being just another statistic: one of the 64,000

Americans that die from overdosing on opioids every year, with numbers only

rising (Pratt, Santhanam). Maresca says, "I had built [the drugs] to be

such a monster in my mind that when [I tried them] … [they were] so opposite of

what I had built it up to be that it almost took me by surprise" (Pratt).

Shockingly, the amount of deaths associated with opioid abuse exceed

those who die from vehicle-related accidents, and gun homicides in a year

combined (Santhanam). In October of 2017, president Trump declared the

opioid crisis “a national, public emergency under federal law,” which displays

the extreme prevalence of the opioid issue today (1). While this epidemic is

solvable, it is not only going to take time, but "the mobilization of

government, local communities, and private organizations" to fix (1).

Opioids are pain-relieving medications most commonly prescribed to treat the

one in ten Americans suffering from chronic illness (Pratt). They include

prescribed pain medications such as morphine, oxycodone, codeine, and

hydrocodone; synthetic drugs such as fentanyl; and the illegal drug heroin.

Opioids work in the bodies nervous system by interacting with opioid receptors

that affect the brain’s pleasure system and regulate pain (Carroll). They have

mood-altering effects to reduce one’s emotional response to pain 100 to 1000

times stronger than what their natural hormone levels can do (Pratt). This is

what makes these drugs such powerful and highly addictive painkillers.

Opioid history dates to over 200 years ago when a German chemist discovered a

way to isolate the sap of the opium plant and acquire morphine (“The History of

Opioid Use in the United States”). The findings soon made their way into

prescribed, and over the counter medications, and were often used to relieve

injured civil war veterans of their pain (1). Furthermore, in 1898, Bayer

Company began the production of the “wonder drug,” heroin, which was first used

as a cough suppressant (Moghe). In the 1970’s, opioids such as Percocet and

Vicodin came on the market, and in the 1980’s pharmaceutical companies launched

major campaigns promoting these powerful drugs (1). Perhaps, these

campaigns were prompted by a New England Journal of Medicine article that

stated, "the development of addiction is rare in medical patients with no

history of addiction" (“Inside the Worst Drug-Induced Epidemic in US

History”). These campaigns made doctors very comfortable prescribing such

medications, and patients confident in what they were taking. In 1996, the

opioid epidemic that we face today started with the release of OxyContin, and

from 1995 to 1996 the number of painkillers prescribed jumped by eight million

(Moghe).

Obama explains that the main reason it took so long for the opioid crisis to

become an urgent topic is that for so long the nation viewed it more as a

criminal law problem than a public health issue (“Prescription for Change:

Ending America’s Opioid Crisis”). In 2003, even the government was spending

over a billion dollars more on law enforcement (6.7 billion) than on treatment

(5.2 billion) (1). Today, viewpoints are shifting from regarding opioid

addiction as a crime to understanding that it is a disease (1). The sad, but

true reality of this shift is mainly due to addiction becoming prevalent in

white communities that have more power to facilitate change (1). Sometimes this

power doesn’t come from their actions, but rather the notion that Americans are

more likely to see the opioid crisis as a disease (instead of a crime) when

whites are suffering (1).

Understanding the distinction between dependence and addiction is significant

(“Physical Dependence and Addiction”). In short, dependence is the withdraw one

suffers after stopping a drug and can be easily managed (1). On the other hand,

addiction is a disease that causes compulsion to the point where one loses

control over their life (1). Donald Fleming, who is seeking rehabilitation at

the Jericho House in Sautee, Georgia, says; “I wouldn’t be able to work, drive,

or take a shower… without [my drugs] it was almost impossible” (Pratt).

Therefore, one must understand that drug addiction is “not a moral weakness or

a lack of willpower…”, but “a chronic disease accompanied by significant changes

in the brain” (Hardee). Surgeon General, Vivek Murthey, tells the Washington

Post, “I am calling for a culture change in how we think about addiction”

(Chen). Individuals who become addicted to opioids will tell you that they hate

what has happened to them, but they don’t know a way out. Without their daily

doses of opioids their body will go through painful, and sickly withdraws that

includes vomiting, nausea, chills, fatigue and even depression that can last

for weeks.

The massive numbers of those becoming addicted to opiate drugs favors no single

subgroup (Santhanam). There is no race, sex, rural or suburban residences, or

even age excluded from the equation (1). Anyone can become addicted (1). This

includes the one baby every half an hour in the United States who is born with

Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (withdrawal infants experience

caused by exposure to drugs in their mother) (Martin). However, the

agonizing stress placed on these vulnerable lives begins long before they even

take their first breath. Drugs taken by the mother during pregnancy crosses the

placenta and prenatally causes 55% to 94% of all exposed fetuses to become

addicted in the womb (Smith). Carla Saunders, head neonatal nurse at East

Tennessee’s Children’s Hospital’s Detox Center, explains how those affected

“have really bad jitters... irritability, vomiting, diarrhea, [and] stomach

cramping” (“Drug-Dependent Infants Detox at Tenn. NICU”). The way to relieve

this excruciating pain is to give the babies the narcotic back, and then slowly

wean them off it; a process that can take weeks or even months (Martin). The

even sadder reality is that while mothers of these children were fully aware of

the risks associated with maternally using opiates, sometimes the guilt of this

just wasn’t enough (Martin). The drugs were entirely too powerful. In fact,

nurses working in a neonatal care unit in Indiana report cases where mothers

admit to shooting up heroin in the parking lot right before delivering their

baby (1). Through this, it is plain to see how opioids are so easy to make

themselves a number one priority against all of one’s morals and values.

Not only are children enduring physical pain, but they are also being exposed

to unhealthy and neglected lifestyles at the most critical stage in all human

development -childhood. With lack of adequate guidance and nurturing these

children may face distresses, along with social and behavioral issues for the

rest of their life (“Addiction Affects Everyone”). U.S. Senator, Joe

Manchin, visited Oceana middle school in West Virginia where he was met with

the touching stories of children born into addicted families (1). Perhaps, one

story shared by a twelve-year-old girl exemplifies the awful magnitude of the

opioid crisis (1). Her step-father had held a gun to both her mother and her

own head because of her mother’s refusal to use drugs that he was taking (1).

She ends with the sight of her stepfather shooting himself right after

murdering her mother by injecting her with three rounds of OxyContin (1).

Shanda Lester, the principal of Oceana, explains how many children in

situations such as this one, “don’t know another world exists, and to them,

this is normal” (1). Another child, Ben Horton, suffers from post-traumatic

stress disorder, aggression, and sleep apnea which is largely the result of

horror movies he was made to watch as his father injected himself with heroin

(“The Young Victims of America's Opioid Epidemic”). It seems unfair how such

innocent lives must experience tragedies that many of us never even will.

Lacking sturdy foundations at home can also put these children at a disposition

for drug or alcohol abuse later in life.

Furthermore, these children are usually pried from the unstable hands of their

addicted guardian (or guardians), and will contribute to the foster care

system’s flooding new faces (Simon). In 2015, about 274 thousand children

entered foster care in the United States, and in less than a year, this number

grew to 437 thousand (“Opioid Crisis Straining Foster System as Kids Pried from

Homes”). While welfare agencies are working as hard as they can, the demand for

homes and resources has gotten so large that in some cases kids are being

placed to sleep in social workers offices (Lachma). Others are having to move

from home to home, never allowing them time to make any real connections

(Simon). These children face worsening feelings of neglect as time progresses,

and it is making the opioid crisis that much harder on everyone.

Social issues directly related to the opioid epidemic are drowning this country

not only in humanitarian aspects, but also America’s economy through an

increase in both criminal justice and healthcare costs, as well as straining

the job market. In the twenty years before 2013, statistics estimate that the

lives lost associated with the opioid crisis cost all economic factors of the

economy nearly 78.5 billion dollars (“How the Opioid Epidemic Affects the

Economy”).

The increase in crimes that the government is cracking down on is primarily

fueled by the eighteen percent of convicted criminals who are trying to obtain

money to purchase street drugs, and the gang-related incidents involved in the

illegal drug trade (“How the Opioid Epidemic Affects the Economy”). Individuals

are stealing by breaking into homes and participating in violent acts to feed

their addiction. In addition, to house and feed incarcerated drug offenders, it

is costing every taxpayer about fifty-two dollars annually (“How the Opioid Epidemic

Affects the Economy”). Georgia’s Drug Detox Organization says, “Even if you

don’t know someone currently abusing or addicted to opioids...it is an absolute

fact that the epidemic has affected your life through your wallet” (1).

Medical care costs have also increased at alarming rates. Insurance companies

pay out, on average, five times greater for opioid abusers than those who do

not abuse them (“How the Opioid Epidemic Affects the Economy”). Also, the cost

of treatment for those abusing opioids including detox centers, rehabilitation,

and medication amounts to about $20,000 per person (1). The economy is also

taking a hit by the increasing demands for nurses, doctors, and medical

supplies as the opioid crisis worsens (1).

Lastly, the ravaging effects of this drug crisis are contributing to struggles

within the job market including rising worker’s compensation costs, and the

lack of healthy and willing employees (“How the Opioid Epidemic Affects the

Economy”). In fact, these issues are estimated to cost employers $25.5 billion

annually (1). There are many reasons that individuals who abuse painkillers

often are unemployed, or not even looking for a job. Those at risk of failing

drug screenings won’t apply in the first place, and often feel it is easier to

ask others or engage in crime for money. An addict interviewed in a VICE

documentary says, “...I give everything to the disease... and I wind up on the

street with no friends, no family, no one to turn to” (“Fentanyl: The Drug Deadlier

than Heroin”). Furthermore, those who do work, and abuse painkillers typically

have trouble holding a job and are often too dope sick to even function while

there. This can then lead to an increased risk of workplace injury. Today, many

companies have done away with their drug testing system (Noguchi). Nate Miller,

the owner of Express Employment Professionals that places workers at local

manufacturing companies says, “it’s not necessarily the best practice, but it

is something that they do because they need people, and they need them so

badly" (1). Not only are companies struggling to find workers, but

sometimes when they do these workers are participating in illegal activity

while on the job (1). Metal parts maker Mursix Corporation, for example, caught

300 employees dealing drugs on their factory floor (1). This hindered the

company’s development by having them refocus efforts on implementing new

procedures to prevent this from happening again (1).

Finding a

solution to this ravaging epidemic is anything but easy. There is no one

overlying approach for solving it; however, it is evident that involvement from

all areas of society and across the entire nation is crucial. Solving this

opioid crisis requires efforts toward treatment solutions for those already

addicted, as well as attention towards preventing people from becoming addicted

in the first place. Currently, the two main options for patients who seek help

include medical assisted treatment and detoxification.

You may feel uneasy to learn that many physicians who are “supposed to be

saving our lives,” are actually causing us harm (“What Can Solve the Opioid

Epidemic in America?”). Many professionals prescribing opiates lack adequate

knowledge of the power of the drugs. Anesthesiologist, Dr. John

Dombrowsk, says anesthesiologists are currently working to educate physicians

and surgeons on great post-operative care (“What Can Solve the Opioid Epidemic

in America?”). Furthermore, many professionals have become conniving in the way

in which they run their practice because their salaries are dependent on their

popularity (1). Because opiates are quick to relieve people of their pain

before they become addictive substances, patients will refer their friends to

the same doctor fueling the same type of treatment (1). No longer can we rely

on professionals to be the ones educated on various treatment options, all

individuals being effected by this epidemic need to acquire substantial

knowledge to work towards solving this issue. Perhaps, an educated

community is the most important component to finding a solution to treating

those who already have been addicted.

Pharma-therapy based treatments, such as the use of Naltrexone, Methadone, and

Sydoxone have become increasingly controversial. Many view this approach as

replacing one drug with another – which sounds contradicting for anyone lacking

knowledge on the reasoning behind it (“Medication-Assisted Treatment Overview:

Naltrexone, Methadone & Suboxone”). These medications work to stabilize the

brain and allow people to feel better in the state of sobriety while having the

energy to support a new healthy lifestyle (“Medication Assisted Treatment

Opiates and Alcohol”). Dr. Edwin A. Salsitz, attending physician in the Mount

Sinai Beth Israel , Division of Chemical Dependency, supports this argument by

explaining that medications “are replacing short acting opioids causing damage

to the brain, with a long acting opioid which aims at stabilizing the brain”

(“Medication-Assisted Treatment Overview: Naltrexone, Methadone &

Suboxone”). Naltrexone works by blocking opioid receptors (“Medication Assisted

Treatment Opiates and Alcohol”). Therefore, if one were to relapse while using

this medication, they will not receive a high (1). Methadone acts as a

replacement therapy that suppresses cravings, lessening the effect of an opiate

withdraw (1). Lastly, Suboxone contains both buprenorphine, which works to

produce less of a euphoric effect when attaching to opiate receptors, and

Naloxone that acts as a blocker (1). These drugs are taken as part of a

complete treatment program which includes regulation, counseling, and

psychosocial support (1).

The main controversy concerning medication as a solution to opioids is due to

the risk of people becoming addicted to the treatment itself. However, by using

proper dosages and working with a licensed practitioner this risk can be

reduced significantly (“Why I Treat Opiate Addiction with Opiates”). In fact,

brain imaging reveals that there is an area of the brain in actively using

opiate addicts that lights up as opposed to those who do not use (“Clinical and

Radiological Findings in Methadone-Induced Delayed Leukoencephalopathy”).

Studies have shown that after 6 months of Methadone treatment, the brain of an

addict can reveal that of someone who does not use (1). This is sufficient

evidence to conclude that while a patient is being treated for their opiate

addiction with medication, the neural issue in their brain is being fixed (1).

Furthermore, Dr. Nora Volkow, director of the national institute of drug abuse

says, “overwhelming evidence shows that Suboxone improves outcomes in people

with opioid use disorders, and that about 32% come clean after 42 months of

[it]” (Macy). This evidence supports that targeting individuals addicted to

opiates through medications may be a realistic way to treat this issue.

Attending a detoxification center, the other most common form of treatment,

requires an individual to have complete abstinence from opioids, leading to

painful withdraw symptoms. Here, the patients are monitored with a doctor on

site, and after their completion they may be admitted into a rehabilitation

program. Dr. John Zipperer, a pain management doctor of over 20 years in

Anchorage, reveals that 97% of those who go into detox end up relapsing, and

this is a reason medicinal therapies are then implemented (“Why I Treat Opiate

Addiction with Opiates”). It seems as if throwing addicts into what is called

“cold turkey” may not be the easiest, nor the most sufficient way to help an

opioid addict.

A solution regarding the

financial side of the opioid epidemic should also be addressed. An article

published in the New York Times revealed how a panel of thirty

experts – made up of credible doctors, directors in drug control and opioid

treatment, and researchers – would spend 100 billion dollars over a period of

five years to solve the opioid crisis (Katz). While there were disagreements

how funds should be divided between treating addiction, and trying to prevent

it in the first place, the consensus revealed four major areas of concern (1).

These areas and their respective percentages of the 100-billion-dollar budget

are as followed: 47% in treatments, including pharma-therapy and attention to the

issue in prisons; 27% for demand that includes education, community

development, and post-incarceration support; 15% for harm reduction towards

areas such as Naloxone carrying requirements, surveillance, and drug checking;

and 11% on supply aspects such as prescription monitoring, police forces, and

interdiction (1). The panel also conversed on the significance of combatting

the divisions between public health, and law enforcement (1). Ultimately, the

nation needs to focus their efforts on individuals needing help, rather than

spending time in disputes against one another.

Another approach to a solution

is for physicians to encourage alternative treatments instead of immediately

prescribing opioids for their pain. One approach is an immersive video game developed

under Dr. Hunter Hoffman, a research scientist in medical engineering at the

University of Washington School of Medicine, called “SnowWorld” (Hellerman).

Hoffman conducted experiments in healthy volunteers using a metal device that

calibrates and cautiously delivers heat to the brain that it interprets as

“pain” (1). The results reveal that pain is reduced by 30%-50% through

distracting the mind (1). Hoffman says, “...pain requires attention, and for

some reason, going into the computer world takes a lot of attentional

resources” (1). Currently, “SnowWorld” is being used by burn patients at

Harborview and Shriners Hospital for Children in Galveston, Texas (1). More

technologies such as “SnowWorld,” may help many cope with painful chronic

conditions and regular appointments that require uncomfortable physician work.

Another therapy, the

implementation of Colorado’s Alternative to Opioids Project (ALTO), is also on

the rise (“Colorado Opioid Safety Pilot Results”). In a six-month pilot

project conducted in 2017, ten hospitals located in Colorado implemented the

ALTO project into their emergency rooms (1). This approach combines the use of

trigger point injections guided by ultrasounds, nitrous oxide, non-opiate

patches, and non-addictive anesthetics for pain (1). The goal of the project was to decrease first-line treatment for

opioid use by fifteen percent, and the results were overwhelming (Daley). The

hospitals were successful in cutting down opiate use by an average of 36

percent (1). In fact, this number amounts to 35,000 fewer opioid

administrations than the same six-month period in 2016 – a number that can have

significantly positive effects on the reduction of opiate overdoses and

addictions (“Colorado Opioid Safety Pilot Results”). Claire Duncan, a clinical

nurse coordinator in the Swedish Medical Center emergency department hospital

in Colorado, describes how a cultural change is needed (1). She comments that

physicians and staff have to change their conversations with patients to model

ways to “treat your pain to help you cope with your pain to help you understand

your pain,” rather than just discussing medication (Daley). Dr. Don Stader, an

emergency medicine doctor and associate medical director at Swedish Medical

Center in Englewood, Colorado, makes a powerful statement as he quotes, “...I

think if we did put this [ALTO] in practice in Colorado and showed our success

that this would spread like wildfire across the country” (1). It is evident,

that long-standing physician prescribing behaviors need to be restructured

towards resolving the opioid epidemic. If implemented across the nation, ALTO,

could be one of the largest factors in solving this alarming crisis.

Camus and Absurdity

Albert Camus, confronted one of

the fundamental questions of life: the problem of suicide (“Camus: The Absurd

Hero”). He wrote, "There is only one really serious philosophical

question, and that is suicide. Deciding whether or not life is

worth living is to answer the fundamental question in philosophy” (1). In

relation to opioids, Camus would comment that they are absurd because people

continue to rely on them and search for a meaning of life through their

effects. He would agree that those who use opiates, in an abusive manner or

not, are ultimately trying to fight their pain and prolong their inevitable

death. Camus believes that once the absurd has been recognized, there are three

ultimate choices one can make: committing suicide; revolting against the

absurd; or distracting themselves from what is happening (“Camus: The Absurd

Hero”). In the case of the opiate epidemic, this respectively means a person

who is addicted can: end their life because their chronic pain and the

miserable path associated with opiates is too much to withstand; try to resolve

their opiate use manage pain through alternative treatments; or continue to use

opiates, never wanting to address that their addiction is in fact an issue. By

Camus’s philosophical ideas, the opioid epidemic could never be solved because

the diversity of this this nation will not allow it (“Camus: The Absurd Hero”).

He thinks that because the world is searching for so many answers, there is no

ultimate answer to settle the chaos associated with the epidemic. According to

him, professionals are wasting their resources by spending millions of dollars

searching for a solution to the opioid crisis- one that they will never find.

Camus would also affirm that through the opioid crisis, people are finding

their reasoning through life in areas such as faith and illusions when in fact

they are just intrinsic comforts.

The opioid epidemic is leaving

thousands of families, and friends each year devastated by the loss of a loved

one. No longer will the joys in life be able to be celebrated in their

presence, nor will memoires be made with them. Opiates, what once were

marketed as non-addictive and safe, have proven to ultimately control anyone’s

life, effecting humanitarian and economic areas of the entire nation. Finding a

solution to this epidemic is urgent, and everyone is desperate for answers.

Ending this plague is going to take the effort, and collaboration of the

“government, local communities, and private organizations” in finding

alternative treatment options, and educating one another (Santhanam). If we do

not continue to address both treatment and prevention options associated with

opiates, the toll it may take on society will be unimaginable.

Works Cited

“Addiction Affects Everyone.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, www.pbs.org/video/addiction-affects-everyone-43qm7x/.

“Camus: The Absurd

Hero.” YouTube, 26 Jan. 2015, youtu.be/aAb7nwtHvTU.

Carroll, Aaron. The Science of Opioids.

Chen, Angela. Addiction Is a Brain Disorder, not a Moral

Failing, Says Surgeon General. 17 Nov. 2016.

“Clinical and Radiological Findings in Methadone-Induced Delayed

Leukoencephalopathy.” Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine - Clinical and

Radiological Findings in Methadone-Induced Delayed Leukoencephalopathy - HTML,

4 June 2014.

“Colorado Opioid Safety Pilot Results.” The Colorado

Opioid Safety Collaborative, 2017, pp. 1–11.

Daley, John. “Ten ERs In Colorado Tried To Curtail Opioids And Did

Better Than Expected.”Kaiser Health News, 23 Feb. 2018,

khn.org/news/ten-ers-in-colorado-tried-to-curtail-opioids-and-did-better-than-expected/.

“Drug-Dependent Infants Detox at Tenn. NICU.” ABC News, ABC News

Network, abcnews.go.com/Nightline/video/drug-addicted-infants-detox-tenn-nicu-16759741.

“Fentanyl: The Drug Deadlier than Heroin.” 22 July 2016.

Hardee, Jillian. “Science Says: Addiction Is a Chronic Disease,

Not a Moral Failing.” Is Addiction a Disease? Science Says

Yes, 19 May 2017.

Hellerman, Caleb. “Finding Alternatives to Opioids.” PBS,

Public Broadcasting Service, 31 Aug. 2017, www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/next/body/opioid-alternatives/.

“How the Opioid Epidemic Affects the Economy.” Georgia Drug Detox,

3 Oct. 2017, georgiadrugdetox.com/resources/opioid-epidemic-affects-economy/.

“Inside the Worst Drug-Induced Epidemic in US History.”

Performance by Rick Leventhal, 10 Apr. 2017.

Katz, Josh. “How a Police Chief, a Governor and a Sociologist

Would Spend $100 Billion to Solve the Opioid Crisis.” The New York

Times, The New York Times, 14 Feb. 2018, www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/02/14/upshot/opioid-crisis-solutions.html.

Lachman, Sherry. “The Opioid Plague's Youngest Victims: Children

in Foster Care.” The New York Times, 28 Dec. 2017.

Macy, Beth. “Addicted to a Treatment for Addiction.” The

New York Times, The New York Times, 28 May 2016.

Martin, Nick. “Babies Born Hooked On Heroin: Special

Report.” Sky News, 7 Sept. 2015,

news.sky.com/story/babies-born-hooked-on-heroin-special-report-10347175.

“Medication Assisted Treatment Opiates and Alcohol.” 1 Apr.

2016, www.youtube.com/watch?v=2CIqcEqsjoE.

“Medication-Assisted Treatment Overview: Naltrexone, Methadone

& Suboxone.” 17 June 2013.

Moghe, Sonia. “Opioids: From 'Wonder Drug' to Abuse

Epidemic.” CNN, Cable News Network, 14 Oct. 2016.

Noguchi, Yuki. Opioid Crisis Looms Over Job Market, Worrying

Employers and Economists. 7 Sept. 2017.

“Opioid Crisis Straining Foster System as Kids Pried from Homes.”

NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, 12 Dec. 2017.

“Physical Dependence and Addiction.” The National

Alliance of Advocates for Buprenorphine Treatment, www.naabt.org/addiction_physical-dependence.cfm.

Pratt, Savannah, director. Addicted: The Opioid Epidemic. 2

Dec. 2017.

“Prescription for Change: Ending America’s Opioid Crisis.” 11 Oct.

2016, www.mtv.com/episodes/heir4r/prescription-for-change-prescription-for-change-ending-america-s-opioid-crisis-ep-1.

Santhanam, Laura. “WATCH: Donald Trump Declares Opioid Crisis a

Public Health Emergency.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, 26 Oct. 2017.

Simon, Scott. “The Foster Care System Is Flooded with Children Of

The Opioid Epidemic.” NPR, 23 Dec. 2017.

Smith, Fran. “Babies Fall Victim to the Opioid Crisis.” National

Geographic, 19 Oct. 2017.

“The History of Opioid Use in the United States.” Performance by

Dr. Andrew Kolodny, 19 Apr. 2017.

“The Young Victims of America's Opioid Epidemic.” The Wall

Street Journal, Dow Jones & Company, 15 Dec. 2016.

“What Can Solve the Opioid Epidemic in America?” Fox

Business, Fox Business, 8 Aug. 2017,

video.foxbusiness.com/v/5535704186001/#sp=show-clips.

“Why I Treat Opiate Addiction with Opiates”. 11 July 2015.

No comments:

Post a Comment